The Squatter Years: Recovering Dorich House Museum’s Recent Past

Project volunteers Verity and Lydia positioning an architectural plan ready for digitising in the photography studio at Kingston School of Art.

THE SQUATTER YEARS: RECOVERING DORICH HOUSE MUSEUM’S RECENT PAST

Close to fifty volunteers have been involved in The Squatter Years: Recovering Dorich House Museum’s Recent Past project since it launched last summer, and many are continuing to research, write and create during the lockdown. Funded by the National Lottery Heritage Fund, the project is divided into three key avenues of investigation. Below, we highlight just some of the discoveries made so far as part of the project.

The Lost Russian Collection

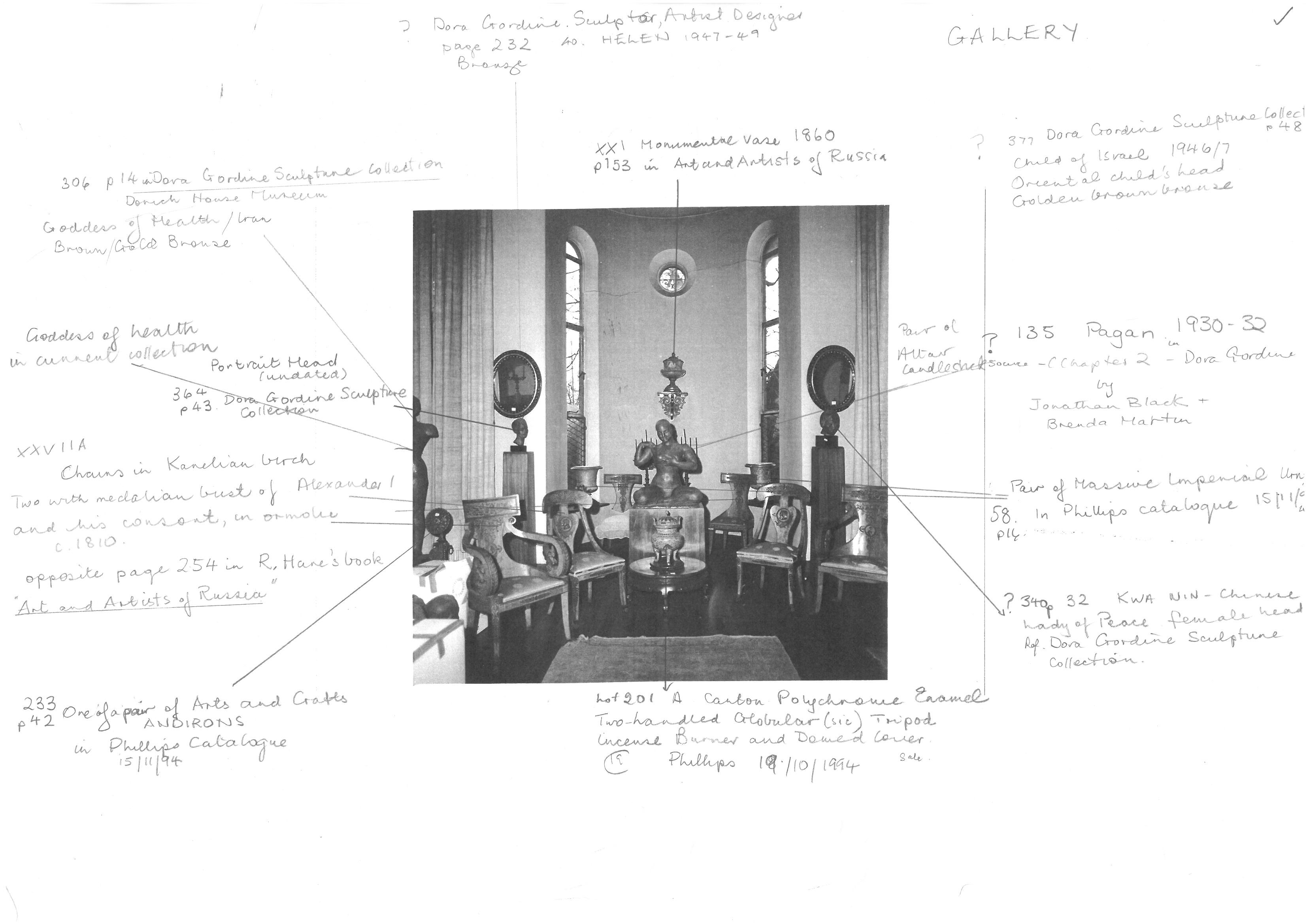

Using historic photographs of the Dorich House interiors, our volunteer Urszula has been identifying objects from Gordine and Hare’s collection that no longer form part of the museum collection, among them a Chinese incense burner (in the centre) that was sold at auction in 1994 which Gordine displayed for many years in front of her bronze sculpture ‘Pagan/Femina’ (1930–32).

When the sculptor Dora Gordine died at the age of 96 on 29 December 1991, Dorich House was filled with her sculpture, paintings and drawings. It also contained an extensive collection of objects, mainly of Russian origin, that she and her late husband the Hon. Richard Hare had collected during their marriage, to which she added after his death in 1966. A burglary in 1988 led to significant losses to the collection and in the early 1990s much of what remained was sold at auctions to support the expense of renovating Dorich House. As a consequence, the vast extent of this collection has not been known until now.

With close analysis of a range of materials – including auction catalogues, sales receipts, a New Scotland Yard list of burgled items, as well as photographs taken of the house shortly after Gordine’s death – volunteers are piecing together the full extent of the collection. While it was known to have contained significant objects – among them Russian icons and Fabergé eggs – the extent, for instance, of Gordine and Hare’s collection of Chinese objects and furniture was less apparent and is amongst many new discoveries that volunteers will be writing about in the coming months.

Hidden Histories of Occupation and Use

The Gallery at Dorich House, after it was occupied by squatters, showing works in plaster by Dora Gordine. Photo: Isobel Porter, © Dorich House Museum

The occupation of Dorich House by different people after Gordine’s death has long been the subject of myth and rumour. Newspaper reports and a few photographs in the museum collection reveal that the house was squatted, but who lived there and what did they think about it? There were also rumours of parties at the house, but who organised these and what were they like? Dorich House was also used by the BBC as a set for the Nicolas Roeg film Two Deaths (1995), but how was the house experienced by those on the set, why was it chosen as a location, and what documentation of the film set remains?

Trained by an accredited instructor with the Oral History Society, our volunteers have begun recording oral histories with those people who were involved with these activities and documenting their rich and exciting stories. Interviewed just prior to lockdown last month, Omar Karmi, who visited the squat in the early 1990s, recalled:

“There is something quite magical about it [Dorich House] – in the sense that it is unique and it has all these levels to it – and at the time, I remember, you’d wander round and there was still a lot of the art work [by Gordine] – whether it was the models or the art work itself – still around, so there was this kind of fairy-tale, adventure-land feel to it, you know? You’d go to another room and you wouldn’t really know what to expect and what you would see, and that was also helped by the slightly carnivalesque nature of the people who lived here and the things that were going on.”

These oral histories are beginning to form the basis for further research, writing and creative responses from our volunteers and will also be added to the museum’s archive.

Renovation of Dorich House

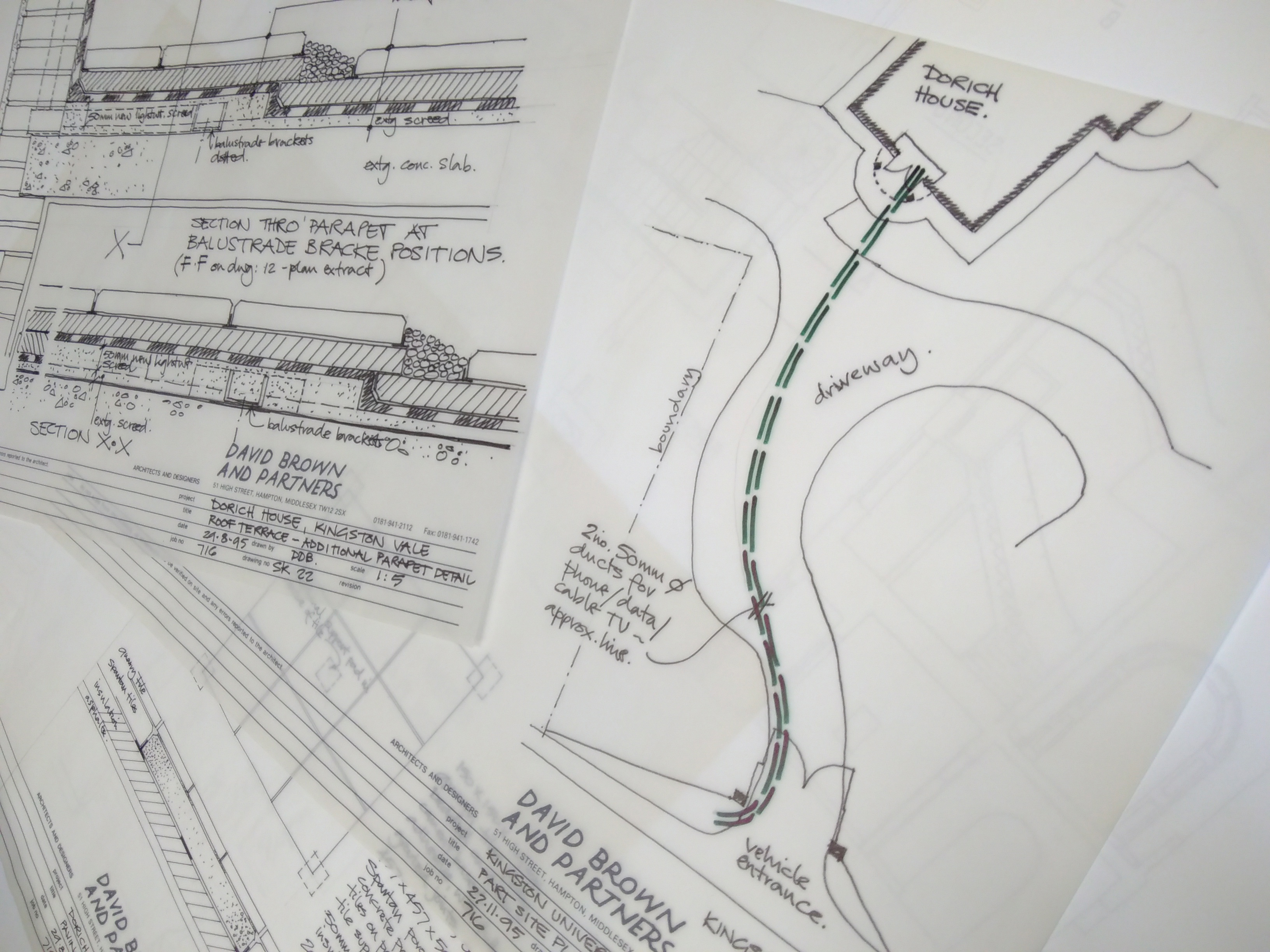

Architectural plans of Dorich House by David Brown and Partners, 1995. Courtesy David Brown and Partners.

Before Dorich House opened as a museum in 1996, the house required substantial renovation, which was entrusted to the architectural practice David Brown and Partners. The practice donated its architectural plans and records from the renovation to the museum archive and, with training by our project archivist, Nancy Lyons, our volunteers have been photographing and cataloguing the architectural plans. Staff at Kingston School of Art’s state-of-the-art photography facilities have also supported them to develop their skills in digitising the plans and records. Through oral-history interviews, our volunteers are also recording the memories of those involved in the renovation and the changes and interventions made to the house and garden since it was built in the 1930s.

Our project volunteers include members of the local community and postgraduate students on programmes at Kingston School of Art including MSc Historic Building Conservation, MA Museum and Gallery Studies and MA Art Market & Appraisal. As the project progresses, we will make more of the research and digitised materials available on our website.

We are continuing our oral-history project during lockdown using remote recording technologies. If you or someone you know has a story to share – however slight – we would love to hear from you. Please get in touch by emailing dorichhousemuseum@kingston.ac.uk

This update was written by Dr Helena Bonett, Project Coordinator, The Squatter Years: Recovering Dorich House Museum’s Recent Past. To sign up to our mailing list, click here.