Squatting and Raves at Dorich House

Over 2019–20, students from Kingston University studying for an MA Museum and Gallery Studies undertook the module, ‘The Challenge of Change’, inspired by ‘The Squatter Years’ project. Led by senior lecturer and course director, Dr Helen Wickstead, students wrote and produced online exhibits reflecting on the occupation of Dorich House by squatters and ravers after Dora Gordine’s death in 1991. Below, three students from this MA course, James D. Moore, Eleanor Carter-Esdale and Lily Flood explore this history.

James D. Moore

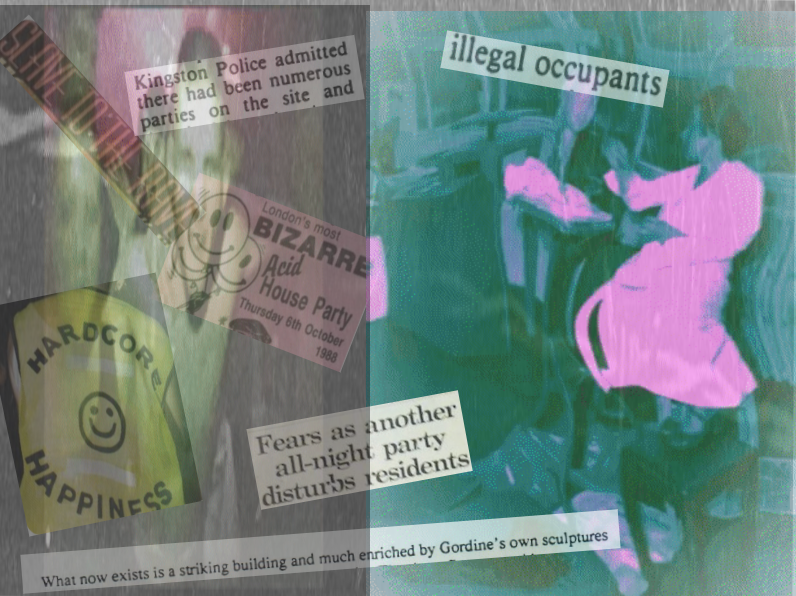

After Gordine’s death in December 1991, and before Dorich House was acquired by Kingston University, the house was squatted, with the Surrey Comet reporting on 4 June 1993 that neighbours ‘are angry that the Kingston Vale landmark, looming out of the hill looking like something from a Hitchcock film, has had its windows broken by intruders’.

The squatters held ticketed raves at the house, but the squat and raves were unpopular with neighbours, who believed that ‘their house values were plummeting thanks to the presence of the illegal occupants’, according to the 18 June Surrey Comet. One anonymous letter writer to the newspaper said that:

‘The squatters have a tent in the middle of the grounds and they light bonfires there.

More importantly, they made an attempt at a rave party and the police were taking the tickets from people outside the gates. Sometimes there is loud music that goes on until 5am.

One of the men down the road is trying to sell his house but he can’t because the viewers keep seeing the tent in the garden and the bonfires.’

The squatters were ‘finally moved on’ that June, according to the same Surrey Comet report. Although, according to our oral histories, squatters and ravers continued to access the house until early 1994.

As part of our module, we explored the Advisory Service for Squatters Archive at the Bishopsgate Institute, the Advisory Service having been established in 1975 to provide practical advice and legal support for squatters and homeless people. Whilst there may be many reasons for people to squat, the most common reason between the end of the Second World War and 1994 was homelessness. During the war, German bombing damaged or destroyed a great deal of London’s housing stock, and construction struggled to meet the demands of Londoners for homes in the decades afterwards. The situation was aggravated in the 1980s by the government’s policy of ‘right to buy’, which allowed tenants to buy their council homes, but did not replace those homes that were sold. Fellow MA student Piroonmas Kajorndechakul and I undertook research at the Kingston History Centre to ascertain views on homelessness, squatting and raves in newspapers at the time. The Surrey Comet reported on 26 March 1993 that ‘As the longest recession in living memory bites ever deeper, the borough’s homeless crisis is spiralling out of control’. A solution to homelessness for some people was to squat in unoccupied property, sometimes with the tacit approval of local councils. Squatting has declined dramatically since it was made mainly illegal in 1994.

Rave music developed out of the Black and gay music scenes in Chicago and Detroit in the 1980s. The electronic and techno sounds were enthusiastically adopted by young adults in the UK in the late 1980s and early 1990s as an alternative to the manufactured pop music or the rock ‘dinosaurs’ that dominated the charts during that period. The music became associated with illicit marathon raves in old industrial sites and warehouses, or outside happenings in the countryside. Psychedelic drug taking was also a part of the rave scene. The government was quick to take steps to ban such unauthorised events. The Criminal Justice and Public Order Act 1994 was enacted to prohibit squatting and ban unlicensed raves.

High house prices and homelessness are still very much contemporary issues. Homelessness is often linked to other social problems, such as poor physical and mental health, unemployment and poverty. The number of homeless people in the UK has risen 165% in the last decade, reported prior to the Covid-19 pandemic which has exacerbated the problem.

Eleanor Carter-Esdale

This work was an attempt at reflecting the coalition of art and experiencing art. I took particular interest in the influence that hallucinogenic drugs might have had on the ravers encountering Gordine’s work. When her work is already so evocative, I wondered how a substance like LSD may have amplified their impact. The visual effects of acid on the taker seem to lean towards the abstract and colourful, a lens through which artwork can be understood and seen on a whole new level.

Lily Flood

A new generation of ravers

A new generation of ravers is an ongoing project collecting the thoughts and feelings of the young people who now popularise the illegal rave scene. An echo of the original raves from the 1980/90s which grew due to austerity, these new events have been rising in popularity since 2016, with thousands of people attending events up and down the country. I was interested in hearing why these young people had chosen these events as a night out instead of the nightclubs that line our high-streets, and why these parties have grown so much in popularity since 2016.

See more of Lily’s work on her website.

Published as part of the project The Squatter Years: Recovering Dorich House Museum’s Recent Past, funded by the National Lottery Heritage Fund, February 2021.